[ad_1]

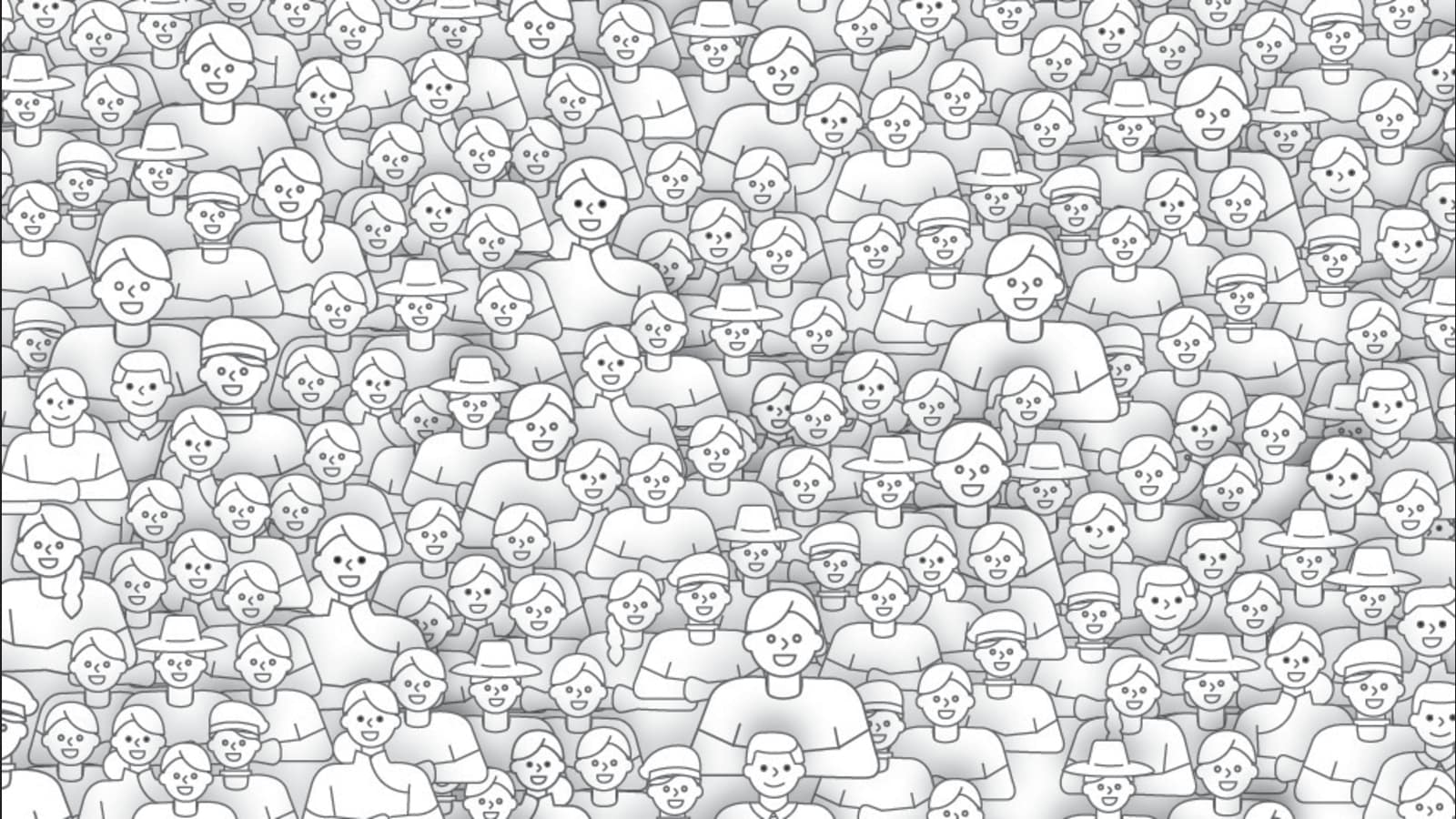

While India worries about its growing population, the world is looking at the entirely opposite problem: This is the century in which the planet will empty out. Countries around the world are seeing a slow, sustained collapse of fertility. Even in places where population is growing—India, North Africa—a tipping point is approaching.

And it’s coming earlier than expected. The United Nations’ 2022 Revision of World Population Prospects estimates that Earth’s population will peak at about 10.4 billion people in the 2080s and remain at that level until 2100. But new data from individual censuses and localised studies shows that it could peak at 9.5 billion people, as early as the late 2050s, and decline sharply after.

This means that for most of us, change will come in our lifetimes. “The children born today will inherit a vastly different world by the time they enter the workforce,” says sociologist and demographer Sonalde Desai, director of the National Data Innovation Centre at the National Council of Applied Economic Research.

A future with fewer people is not, by itself, a good or bad thing. More people now live in cities, and small families may be more efficient where living costs are high and where many hands are not needed for farm work. Lower fertility rates within a community also indicate gender equality; better educated women typically have fewer children, later in life. In countries where many people compete for few resources – university seats, jobs, homes in good neighbourhoods — a lower population can come as a relief. Many hope it might even stall the climate emergency (It may not; see the story alongside).

But fewer babies today also mean fewer workers, fewer taxpayers, fewer ideas, fewer drivers of economic growth in the coming years. The World Health Organization estimates that by 2030, one in six people globally will be over the age of 60.

Some countries are simply importing people. Canada, where the population (now 39 million) has declined since 2009, hopes to take in 1.5 million immigrants between 2023 and 2025. But xenophobia is growing. “It’s a growing country, but whose country?” asks Desai. Migration isn’t a catch-all solution either. “Population is also dropping in Haiti and Vietnam. Few want to move there.”

Intimate decision, global repercussion

Demographers see a clear geographical distinction in why couples might want fewer or no kids. “In the West, having children is seen as at odds with the pursuit of individual freedoms. It’s why Nordic countries, with generous parental leave, job security, state-subsidised childcare and other family-friendly policies have had a slower decline than their neighbours,” says Desai. “In East Asian regimes, it’s because kids now require high investment—time, money, school costs, attention, childcare—which leaves out the option for a large family.”

This explains India’s steady decline too. “What works for a family doesn’t always work for the nation,” Desai says. In India, all but five states (Bihar, Meghalaya, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Manipur) already have fertility rates below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman. Families are smaller in the southern states, where ageing folks are already starting to outnumber young people.

The transition defies religion. Census data from 2011 shows that in districts where Hindu fertility was high, Muslim fertility was also high; and where Hindu fertility was low, Muslim fertility was low too. ”There are larger forces at play,” says Desai. Italy’s population has been declining for 14 years, “and this is a Catholic country. Bangladesh, Thailand and Iran now have continuous low birth rates too.” West or East, it seems like having a child has become a value proposition in a way it’s never been before.

From cradle to crucible

Historically, dips in human population have come from famine, plague and war. Biologically, most species tend to have more offspring when they have access to greater resources. The current decline bucks both trends.

Don’t blame women. Family-size decisions are a couple’s choice. “Society expects so much more of mothers everywhere in the world that we have what American sociologist Annette Lareau calls Concerted Cultivation,” says Desai. It means that parents funnel the time, effort and money they’d have spent on more kids into just one or two, raising them, in Lareau’s words “like hothouse flowers”, in sync with the demands of the professional world.

In India, fall in family size hasn’t coincided with growing women’s participation in the labour force. It’s largely because institutional structures are still not family friendly. “We talk and talk about how men need to be involved in housework. But workplaces haven’t accommodated the idea that child-bearers and child-rearers are part of the team,” Desai says. “It isn’t just keeping women away, it’s harming future generations.”

Governments are trying a bit of everything to stabilise populations. Some have invested in expensive labour policies so couples don’t have to choose between careers and children. Others offer incentives for women to just stay home, have kids and raise them. Still others have discouraged family planning altogether. See how it’s all playing out.

.

BALANCING ACT

Take a look at measures adopted to try to stabilise populations in countries around the world.

(All population and fertility rate data from 2021, via data.un.org/en/index.html)

.

RECEDING HEIRLINES

What coming generations will inherit

2.8 billion: Earth’s population in 1955. Today, that is the population of India and China alone.

9.7 billion: Earth’s population by 2050, according to estimates by the United Nations Population Division.

134 million: The number of babies born worldwide in 2023. That’s an average of 367,000 newborns each day. While this may sound like a lot, it is actually the lowest number of newborns since 2001.

61 million: The number of deaths in 2023. This means global population rose by 73 million people last year, a net increase of 0.91%.

20.3 years: The median age of a human in 1970. It means that half the population was older and half was younger at the time.

30 years: The median age of a human on Earth right now. Fewer births and a longer life expectancy means this is the oldest median age in history.

2080s: The UN’s projections of when human birth-death numbers will even out, making global population peak. There will be an estimated 10.4 billion people on Earth, with no decline until 2100.

2050s: The projection from some demographers on when population will peak, based on data from nations showing early declines. They estimate that human population will stand at 9.5 billion, and drop sharply thereafter.

.

Why is a population’s replacement rate set at 2.1?

The figure represents the number of children a woman is likely to have in her lifetime. Mathematically, a fertility rate of 2 means there are as many kids as parents, that family sizes remain the same and, barring migration, there is no growth or reduction in the population from generation to generation. The 0.1 is added to offset infant mortality

But with sex-selective abortion prevalent in many cultures, not all girl children survive or make it to their fertility age. So when demographers calculate figures for the planet as a whole, they use 2.2, to account for the gender imbalance. The fertility rate for humanity is already at 2.2. For the very first time in human history, we are not reproducing ourselves.

[ad_2]

Source link