[ad_1]

Members of Gambia’s National Assembly have proposed legislation to repeal a national law prohibiting female genital mutilation (FGM).

The tiny West African nation explicitly criminalized FGM, also called cutting or female circumcision, in 2015. The law states that: “A person shall not engage in female circumcision. … A person who engages in female circumcision commits an offence.”

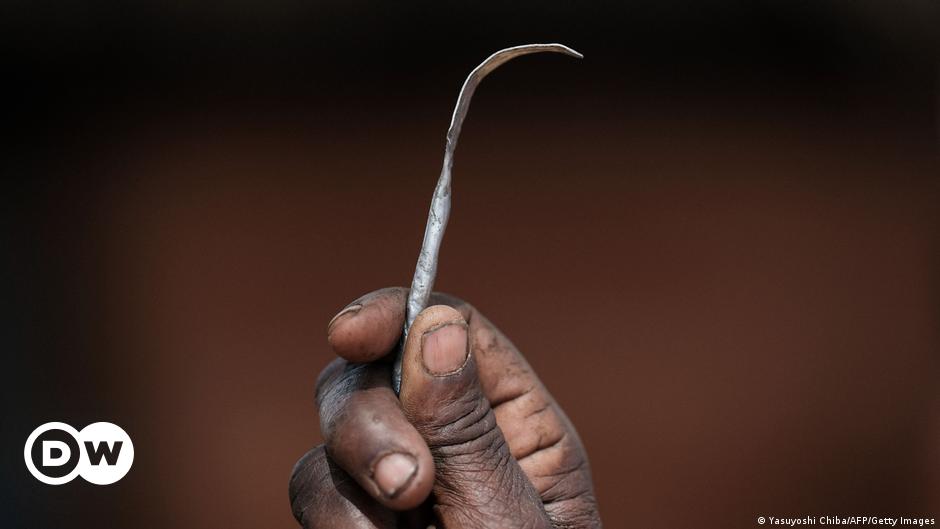

FGM involves partial or totally cutting of the female external genitalia. It often involves the removal of the clitoris or labia. It has no health benefits and harms girls and women in many ways.

In The Gambia, carrying out the procedure is punishable by up to three years in prison, a fine of 50,000 dalasi ($736 or €674), or both, and where FGM causes death, life imprisonment.

Debate around criminalizing FGM

The debate around FGM flared in mid-2023 after three women were convicted under the law. They were ordered to pay a fine of 15,000 dalasi or serve a year in jail for carrying out female genital mutilation on eight infant girls aged between four months and one year.

These were the first convictions under the law. Prior to this, only two people had been arrested and one case brought to court, according to UNICEF, and no convictions or sanctions had been handed down.

This is despite nearly three out of four girls and women, or 73%, having undergone female genital mutilation in The Gambia.

Most of the country’s population are Muslim, and many believe that FGM is a requirement of Islam.

Isatou Touray, former vice president and founder of the anti-FGM organization GAMCOTRAP, strongly refutes this interpretation.

“Who has the right to interfere in what Allah had created, and who has the right to define how a woman should look?” Touray told Gambian media organization Kerr Fatou.

The private bill, proposed by individual members of parliament, to scrap the law outlawing FGM argues that the current prohibition violates citizens’ rights to practice their culture and religion.

Supporters of FGM believe it can “purify” and protect girls during adolescence and before marriage.

“When it comes to the social aspect, they’ll even tell you, ‘Oh, it is to ensure that you stay a virgin because if you have the clitoris then … you would want to have sex,” woman’s rights advocate Esther Brown said in an interview on DW’s AfricaLink radio program.

Human rights violation

The practice of FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women, finds the World Health Organization.

As well as severe bleeding, FGM can cause a variety of severe health problems, including infections, scarring, pain, menstruation problems, recurrent urinary tract infections, infertility and complications in childbirth.

One study on the health consequences of FGM in Gambia found women who were cut are four times more likely to suffer complications during delivery, and the newborn is four times more likely to have health complications if the mother has undergone FGM.

Parliamentary reporter Arret Jatta told DW that she wasn’t surprised that the pro-FGM bill has come before parliament, given the heated discussions in the past months.

“Almost all the National Assembly members are in support of the law being repealed especially the female National Assembly members,” she said. “If it’s repealed, then I’m still not surprised.

It’s not just politicians who support rolling back the FGM ban. After the three women were convicted last year, an imam paid their fines, and the Gambia Supreme Islamic Council issued a fatwa declaring FGM more than an “inherited custom … . Rather, it is one of the virtues of Islam.”

“Let them not jail our mothers,” Iman Alhaji Kebba Conteh told DW as parliament discussed the bill on Monday. “We do not like them to take our wives and jail them.”

But for Fatima Jarju, an FGM survivor who sensitizes women in Gambia to the harms of the procedure, the debate is damaging women’s rights.

“I think it’s a big setback,” she told DW. “And also looking at our human rights standards as a country and also the commitment from the government to protecting the rights of women and girls of this country.”

Legislation not always effective against FGM

The Gambia is among 28 sub-Saharan nations where FGM is practiced. Six of these nations lack a national laws criminalizing the procedure (see map below).

The Gambia, whose parliament will discuss the pro-FGM bill again later this month, could soon join them.

Many anti-FGM activists stress, however, that legislation alone is insufficient to tackle FGM, especially when it lacks enforcement, as is the case in The Gambia.

Rugiatu Turay in Sierra Leone, one of the six African nations without a law against FGM, has gained international recognition for her work combating FGM.

The strategies she uses include the development of rites of passage for girls that don’t involve cutting, finding alternative livelihoods for the cutters and intense community engagement.

She isn’t convinced that legislation is the best way to tackle the issue.

“Generally, in Africa, people make laws to satisfy their donor partners. But when it comes to implementation, they are not implemented,” she told DW.

To change cultural attitudes, she says, more community-based initiatives are needed that involve everyone from regional chiefs, local headmen and religious leaders to the cutters and the mothers making decisions for their daughters.

“If every sector in our country speaks about the cut and the scar — and its consequences — I tell you, we will end FGM,” she said.

Sankulleh Janko in Banjul, Eddy Micah Jr. and George Okach contributed to this article.

Edited by: Rob Mudge

[ad_2]

Source link