[ad_1]

Just about a little more than 1.8 crore new voters (18-and 19-year-olds) are on the electoral rolls, according to data put out by EC after poll dates were announced about a fortnight ago.

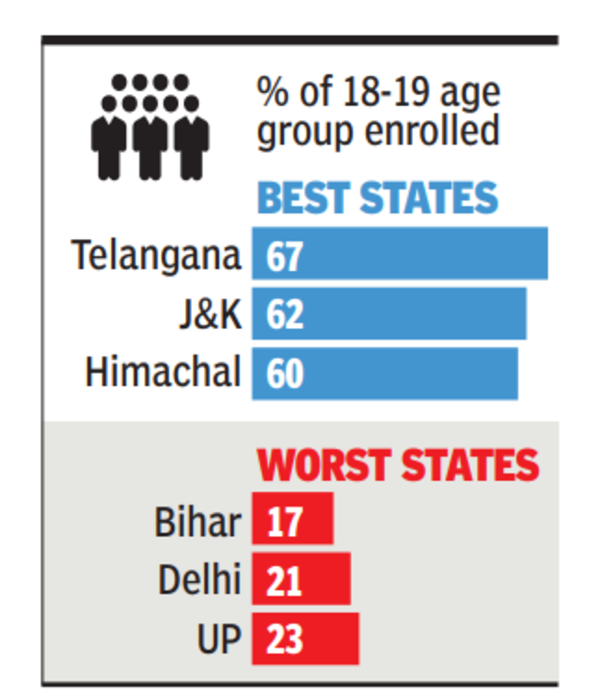

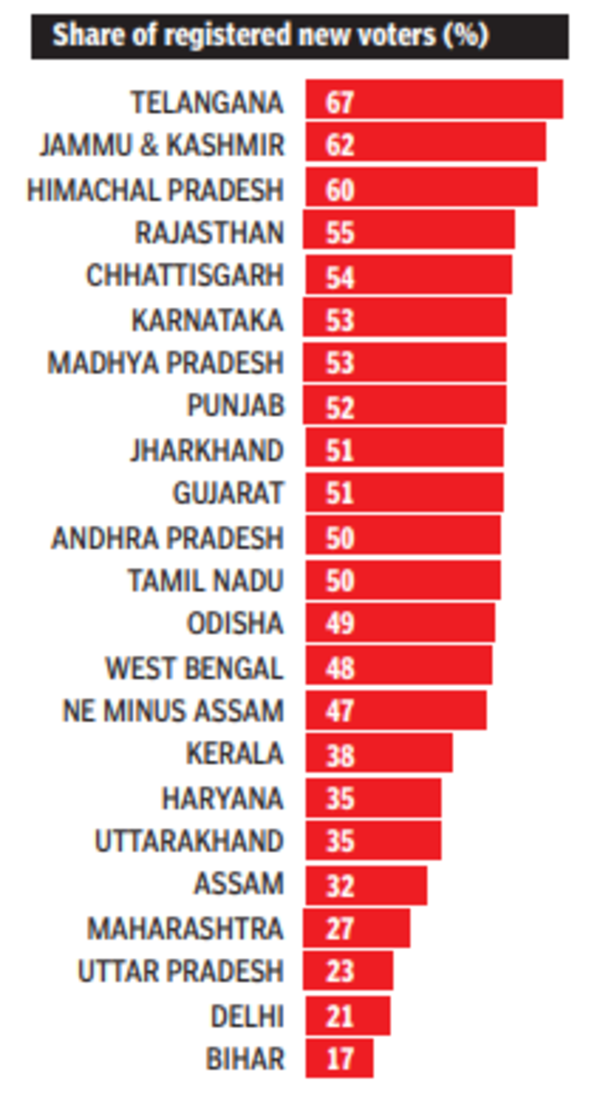

The projected population in this demographic is just under 4.9 crore, which means barely 38% of these first-time voters are on the rolls. Telangana tops the list with over 8 lakh (66.7%) in the 18-19 age group enrolling. Bihar is at the bottom of the heap with just 9.3 lakh (17%) enrolled from a potential 54 lakh.

Only 38% of thosewho turned 18 or 19 have enrolled to vote

The irony can’t be more stark: those who have the highest stake in the future have shown the least inclination in engaging with a process that holds the key to how the future will shape up.

The world’s largest electoral process has begun, but the youngest voters – 18- and 19-year-olds – seem reluctant to make their vote count. Fewer than 40% of them across the country have registered to vote in the 2024 elections, with some states — such as Bihar, Delhi and UP — seeing less than a quarter enrolling.

Just about a little more than 1.8 crore new voters (18 and 19-year-olds) are on the electoral rolls, according to data put out by the Election Commission after the poll dates were announced about a fortnight ago. The projected population in this demographic is just under 4.9 crore, which means barely 38% of these first-time voters is on the rolls. The number could, of course, go up a fair bit as the EC, political parties and various civil society groups are doing their bit to see to it that each eligible voter does register, but just how far can they push it?

The state that seems to have done the best in getting the youngest age group involved is, appropriately, Telangana, India’s newest state — where over 8 lakh 18and 19-year-olds are on the rolls, about two-thirds, or 66.7%, of its projected population of 12 lakh for this age group. J&K and Himachal are two other states/UTs that have managed to enrol 60% or more. At the other end of the spectrum is Bihar, the state with the country’s youngest population, with just 9.3 lakh enrolled from a potential 54 lakh (17%), as is Delhi, with only 1.5 lakh out of 7.2 lakh, just a shade above one in five (21%). UP at 23% and Maharashtra at 27% have not done much better.

The irony is inescapable, given just how much chatter there has been from parties across the political spectrum about youth being key to India’s future and to electoral outcomes.

The data also means that in three of the five largest states in terms of Lok Sabha eats — UP, Maharashtra and Bihar — a quarter or less of 18and 19-year-olds are registered to vote; in the other two — Bengal and Tamil Nadu — less than half have entered the electoral rolls.

How did we get these numbers? We looked at age group-wise population projections done by the Census office for March 2021 and March 2026 and extrapolated from those to arrive at a figure for March 2024 for each of the major states/ UTs and for India as a whole. Since these are projections, they are likely to be a bit different from actual numbers, which we don’t know since Census 2021 is yet to happen. But the estimates would not be significantly off the mark.

Former election commissioner S Y Quraishi, who had been instrumental in starting a voter awareness and education department in the EC in 2010, said he was pained to learn about such low enrolment.

“Voter apathy has always been an issue, but we were able to address it with a sustained campaign,” he said. “But it appears something is amiss. It is a matter of concern that efforts have either slowed down or been ineffective.”

Those working in the field to register young voters say a combination of factors could be responsible for the dismal numbers: apathy of young people and challenges in processing paperwork could be among the main reasons.

Anil Verma, the national coordinator of Association for Democratic Reforms, said informal discussions suggested cynicism about the electoral process. “The apathy,” he says, “could come from a feeling that the leadership of major parties is made up of seniors and that there are not enough young leaders or candidates, to whom young people can relate.”

For “migrant” students and whitecollar workers, there is simply not enough motivation to go through the paperwork hassle, Verma says. For a similar bluecollar worker, it makes even less sense to vote, for she/he would have to forgo a day’s wages to do that. Asked about Bihar’s low young-voter numbers, Rajiv Kumar from the NGO Action for Accountable Governance (AAG), which works on voter awareness, said enrolment had to be sustained throughout the year, not just for a few months before polling. Political awareness is high in Bihar but does not translate to higher enrolment. “There is a large section of the population — students and migrant workers — who migrate and come home only during festivals or holidays. Their enrolment should be done while they are in the city,” Kumar said.

Chaitanya Prabhu from Mark My Presence, which holds workshops in schools and colleges in Maharashtra on issues of civil rights and governance, disagrees about young people being disinterested. Lack of information on the political process and governance issues creates challenges, he says. “Throughout school and college, students live with the perception that politics is a bad word and is best kept at arm’s length as a profession. You cannot suddenly expect them to turn 18 and want to participate in the electoral process,” he said. The basics of elections and politics are not even taught in schools as part of the syllabus, except under CBSE, he says.

Gourav Vallabh, Vijender Singh, Sanjay Nirupam dump Congress party ahead of LS polls 2024

“However, when you explain to young people how the right to vote was won, the process of governance and the significance of being a part of it, there is an overwhelming response to enrol and vote,” Prabhu said. Mark My Presence has enrolled 41,000 new voters this year in Mumbai through its efforts.

There have been efforts by EC, in recent years, to encourage eligible voters to register: awareness campaigns, enrolment camps, using celebrities to spread the word, a 30-hour offline hackathon last year to address apathy, and so on. Parties, too, have made an effort, in their own way by giving tickets to younger candidates.

Chief Election Commissioner Rajiv Kumar mocks social media EVM experts amid laughs

[ad_2]

Source link