[ad_1]

I am told that the earliest example of a big brand trying to offer a small sachet (no, it wasn’t shampoo) in India was Brooke Bond, with its 5-paise pack of tea, launched in the mid-1950s. This was not a tea bag, but tea leaves or tea dust sold in a small paper sachet, meant for a single strong cup of tea.

And while we don’t get single-serve tea leaves in tiny sachets any more (we’ll get to why in a bit), a gamut of products is available in sachets and small packs in India today — in an evolution that can be traced all the way back to a small company from Tamil Nadu.

The product that first caught the consumer’s fancy in this format, and the fancy of celebrated management gurus such as CK Prahalad, was the humble shampoo sachet. Between Velvette and Chik, two brothers from Cuddalore, CK Rajkumar and CK Kumaravel, created a shampoo and sachet revolution in the country, in the 1980s.

Their 50-paise sachets, a format that would come to be called LUP (low-unit packs) or SUPs (single-use packs), were written about in management journals and mentioned in Prahalad’s bestseller The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid (2004).

What these brands, or more specifically Chik (Velvette disappeared a few years after launch) did, was to offer a then-luxury product to middle- and lower-income consumers in an affordable form. At the time, a bottle of shampoo cost about ₹25 and was way out of reach for most consumers.

A detail that often gets ignored in this story is that, in the 1980s, shampoo attracted an excise duty of over 65%. Chik, since it was made in the small-scale sector, did not have to pay this duty. The brand was genuinely cheaper. Even when the no-excise advantage disappeared after liberalisation, consumers kept buying the tiny packs. This forced big brands to offer their own versions. Not only shampoos but numerous products began to be sold in SUPs.

The tiny pack also became a gateway for consumers, who might then graduate to the full bottle, and the LUP / SUP retains this function.

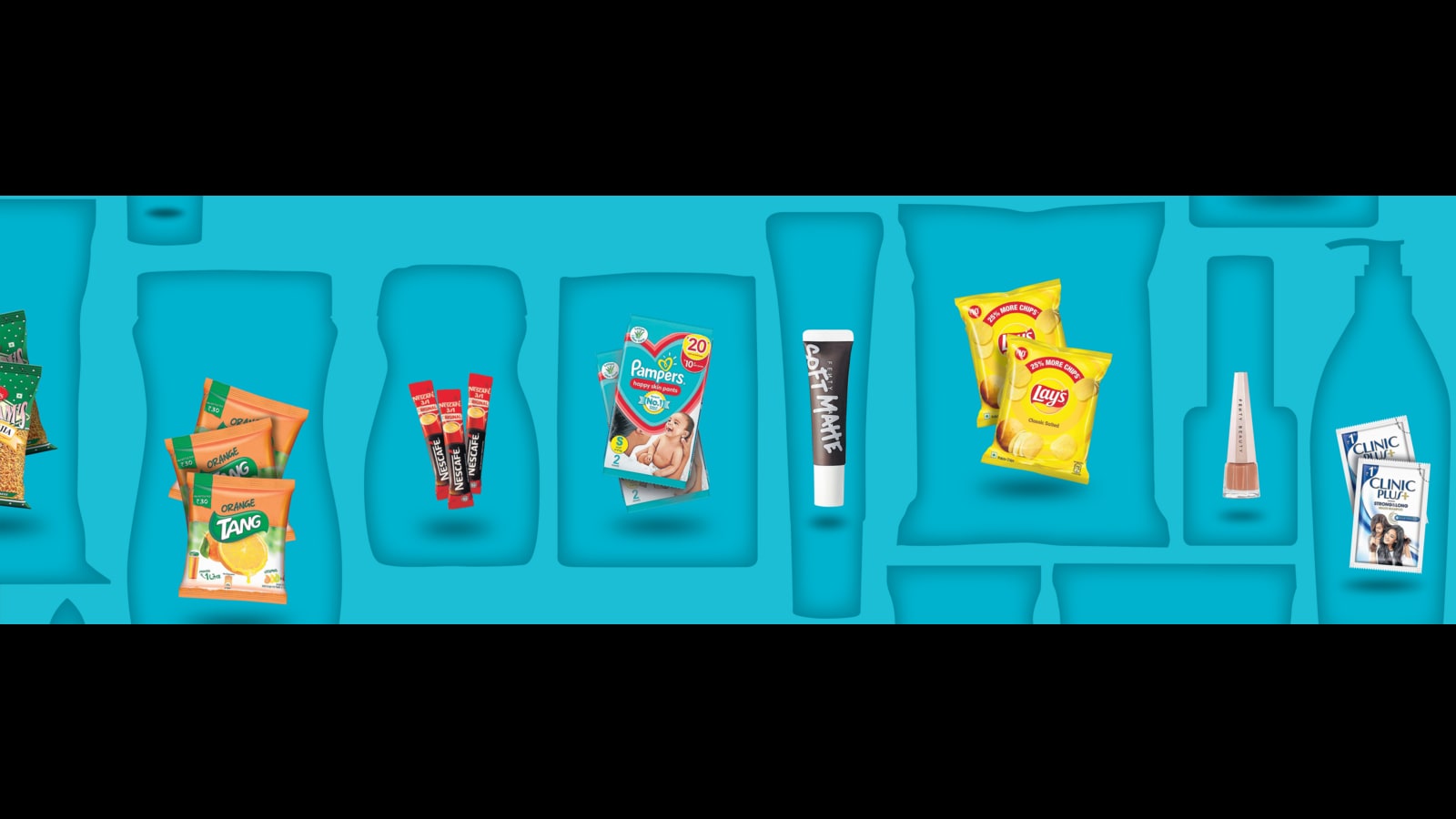

Chips in small packs followed shampoos. Biscuits began offering ₹5 packs by the 1990s. Indian snacks (bhujia, chivda and the like) began to come in tiny, shiny single-serve portions.

My tryst with sachets began in the early 1980s, when I was in marketing at the pharmaceutical major Boots. For a number of companies, including ours, the transition to SUPs wasn’t an easy one. Boots, for instance, sold the cough lozenge Strepsils in aluminium-foil strips of 10, and was facing a new competitive threat: Halls, sold as singles. To add to our grief, Vicks Cough Drops soon followed. Unfortunately, Strepsils could not be sold in single packs because of its formulation. It took considerable effort to reformulate the product and launch it in singles, as Strepsils Icy. Meanwhile, both Halls and Vicks discontinued their carton packs of tens entirely, following the tremendous success of their singles.

In his book The CEO Factory: Management Lessons from Hindustan Unilever (2019), Sudhir Sitapati speaks about how HUL had to create a slightly different formulation for Clear Shampoo, when they wanted to offer it in a small sachet at an attractive price point.

Marico founder Harsh Mariwala has spoken about how his company worked with packaging experts to create the Re 1 “bullet pack” of Parachute coconut hair oil, in the early Aughts. I was a big fan; I always had a few in my travel kit. But the company withdrew the pack about 10 years after it was launched. Not all sachets are a roaring success.

Colgate launched a sachet pack in the 1980s and had a very catchy ad for its “Colgate Ka Chhota Packet”. But that did not find many takers either.

Why did toothpaste and hair oil fail when shampoos succeeded? I have discussed this with experts and the conclusion we have reached is that if a product category has become an essential, then the consumer sees more value in a bigger pack. It is when the product is a bit of a luxury that they want to try the Re 1 packet.

Instant coffee still comes in single-use sachets. Nescafe has in fact expanded its SUP offerings here, to include a wide variety of ready-to-drink concoctions (frappe; chilled latte; iced cappuccino). Once again, I believe this has to do with the fact that coffee is still seen as a luxury in many parts of India, being far more expensive than tea.

***

Today, the world of LUPs is expanding into the luxury-premium space.

Over the past two years, the global cosmetics giant MAC has begun offering its nail enamels and lipsticks in small packs; not the full range of colours, just the most popular ones.

Dove and L’Oreal have taken to tiny packs for face wash and other products. “Premium” brands such as Bobbi Brown and Clinique also offer products in LUPs in India, something that is generally considered unseemly in the luxury-premium branding playbook. Rihanna’s Fenty Snackz is positioning itself entirely as a luxury-premium “bite-sized beauty” brand.

Sanitary pads are available in singles, as are diapers. Milk drinks such as Complan and Pediasure are sold in single-use packs. Fruit-drink concentrates such as Tang are available in sachets.

Kellogg’s offers sachets of its popular Chocos variant and this is said to have been a game-changer for the company, which was struggling to sell the idea of corn flakes dunked in cold milk to a country that loves hot breakfasts. Their pivot to snacks aimed at children, in a small pack, was a daring and ingenious move.

The mission across these products remains the same: to help consumers start their brand journey, just as Brooke Bond was aiming to do in the 1950s. Until tea went mainstream, and those sachets met the fate that the toothpaste and coconut oil ones later would.

Are marketers reaping the big dividends from tiny packs?

LUPs are helping the Indian consumer sample brands with forbidding prices, and are helping them overcome their inertia. This is after all a market of a billion plus Lilliput consumers (as Rama Bijapurkar calls it, in her new book, Lilliput Land) who remain driven by value-for-money propositions, even in the premium-luxury space (for years, Mercedes sold more diesel-powered vehicles simply because diesel was much cheaper than petrol). LUPs also help expand the catchment area to smaller cities and towns.

Could it also work the other way, encouraging buyers of full packs to go smaller? That is something marketers have been known to consider, when launching SUPs of popular brands.

LUPs and SUPs are also often less profitable than the larger packs. This makes for some intricate math from marketers. How small can one go? Which products must never shrink? These become vital questions for a brand, though the answers must take into account the offerings of competitors, which is one reason, for instance, for the current broad shift in the cosmetics space.

An element of on-ground collaboration becomes essential too, and this is where the kirana store owner comes in. He has perhaps the biggest role in encouraging the sampling of new offerings, because his customers trust him. (Scan the QR code alongside for my previous essay on what makes the corner store such a survivor).

It helps that the kirana store owner embraces the new, if it brings good news for his community (and his bottom lines too). What might shrink to tiny next? He’s sure to have an interesting answer.

(Ambi Parameswaran is a brand strategist and the best-selling author of 11 books. His latest, All The World’s A Stage, is a personal branding story)

[ad_2]

Source link