[ad_1]

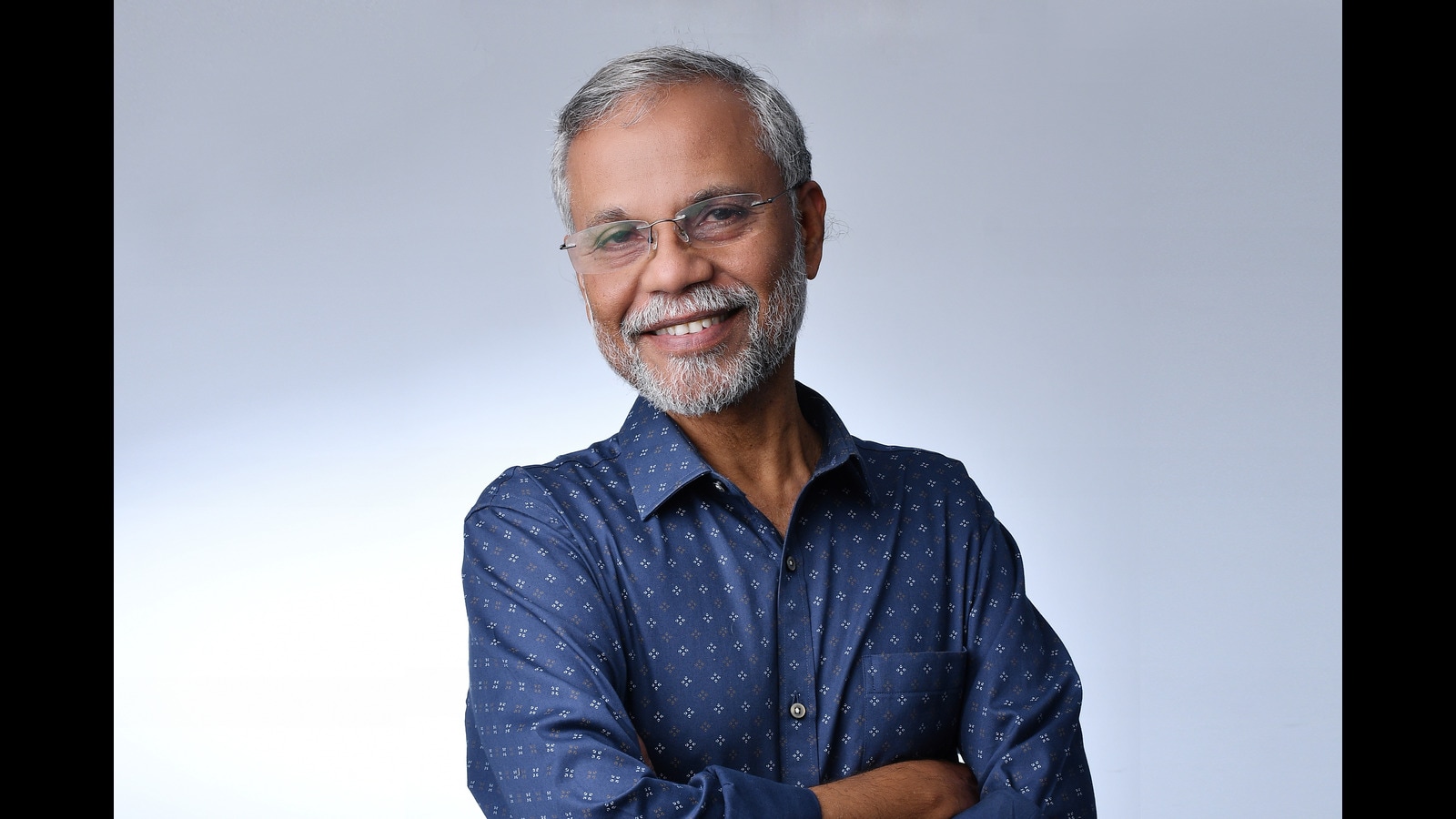

What does success look like, as an environmental policy consultant? Perseverance is the only certain success, says S Faizi. Failing is a big part of the job, he adds. Fighting, continuing to fight, is the mission.

Over three decades, Faizi, 63, has advocated for the recognition of war as an environmental threat, fought for indigenous community rights, campaigned for nuclear disarmament and for the creation of a UN Environmental Security Council.

His work involves fighting, pushing, and continuing to hope, as global powers — political and corporate — push back, and often win.

At the global level, he has represented countries such as Malaysia, Venezuela, Qatar and Saudi Arabia at the United Nations, pushing for international environmental treaties to be fair to the Global South and demand enough of the Global North. He has served as biodiversity advisor to the United Nations Development Programme and is currently serving in this role at the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

In India, he has been biodiversity advisor to forest departments in West Bengal and Sikkim, and developed biodiversity and forest management plans for Gujarat, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh and Tripura.

Three weeks ago, he was one of six recipients of the Planet Earth Award, instituted by the Alliance of World Scientists (AWS) to recognise individuals who “demonstrate exceptional creativity or contributions in their work in science-based advocacy with the public”.

“He has played a pivotal role in articulating the Global South’s stance on key environment and development issues, often overcoming opposition from Western negotiators at UN environmental conferences,” an AWS statement reads.

Faizi remains rather unimpressed by himself. “It’s a lot more exciting to receive these awards when one is younger,” he says, laughing. “However, this comes from a community of scientists, and peer recognition is something I value very much.”

***

Faizi grew up in Thiruvananthapuram, his mother a homemaker and his father an additional finance secretary with the Kerala government. He spent months each year in his family’s village of Poruvazhy in Kollam district, Nearby was the Sasthamkotta Lake, a hotspot for migratory birds. “The area around our village was essentially a forest,” he says.

His desire to protect what he saw can be traced to his days watching rare birds arrive at that lake, he says. While in college in Kollam in 1980, he joined student politics, and heard of the Silent Valley movement — a public campaign that had been underway since the 1970s, opposing a planned hydroelectric plant that would submerge Kerala’s tropical evergreen Silent Valley forest.

This is a biodiversity hotspot that is also home to the largest population of lion-tailed macaques, one of the rarest primates on Earth. Faizi joined the marches, helped spread word, learned more about conservation and forged relationships with seniors within the movement. “I learnt then that there is a unique kind of solidarity that emerges from people with a common struggle,” he says. He would see the movement eventually succeed, with Silent Valley declared a national park in 1984.

This would teach the young activist the power of speaking up, getting help, and refusing to be silenced, as a means of environmental agitation.

His love affair with birds continued, meanwhile. Faizi graduated in zoology, worked as a field biologist under the legendary ornithologist Salim Ali at the Bombay Natural History Society; completed a Master’s; then a PhD in biodiversity management.

He joined the International Youth Federation for Environmental Studies and Conservation (IYF), where he served as secretary general for two years. “That was where I learnt the art of negotiation, and how to navigate international environmental policy and the inner workings of global institutions,” he says. “I worked closely with members of UNESCO and the United Nations Environment Programme, because IYF was considered the de facto youth wing of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).”

As he travelled and engaged with people from around the world, he became incensed by stories of life under Apartheid in South Africa. So, in 1990, Faizi helped organise a protest outside the International Ornithological Congress in New Zealand, where an Apartheid-era delegation from South Africa was present.

He missed the inaugural address by mountaineer Edmund Hillary, who talked about his birding experiences in India during his term as high commissioner. “I really wanted to listen to his speech,” says Faizi. “But the protest was more important.”

***

The most important work he has done so far lies closer home, he says. In 2009, he was part of the committee constituted by the Kerala government to estimate the financial cost of the environmental damage caused by the Coca-Cola plant in Plachimada in Palakkad district.

The plant was accused of overusing and contaminating local water resources, to the severe detriment of the region’s large Adivasi population. It had run for four years, until a 2004 court ruling ordered it to stop drawing on groundwater for its bottling operations.

The case and the idea of compensation drew immense media and public attention. “This was the first time that a committee in India was assigning financial value to environmental damage,” says Faizi. “We didn’t have any models to draw on. We had to develop our own methodology.”

The committee eventually estimated the damages to be in the amount of ₹216 crore, and introduced the Plachimada Coca-Cola Victims’ Relief and Compensation Claims Special Tribunal Bill, which was passed in 2011.

That’s where the good news ended.

The bill waited at the Centre for years, before President Pranab Mukherjee returned it without assent in 2015. Two decades after the plant shut, the residents of Plachimada have still received no compensation.

“In general, when working on the ground in India, science alone isn’t effective. Political influences come in the way. Mysteries crop up. Things are swept under the carpet,” Faizi says.

He has received threatening phone calls for saying things like that. “My wife Nazeema (Faizi, 57, an electrical engineer turned lecturer) took one such threatening call and was alarmed, but I don’t think my life is in any real danger,” Faizi adds. “I have been too outspoken for far too long.”

Two things, for now, give him a sense of victory: a life lived true to the mission he chose; and his family. The Faizis have two children. Their son Iqbal Faizi, 31, is a mechanical engineer and daughter Najma Faizi, 26, a doctor. They are good, kind people who care about their world, he says.

“Iqbal has trekked up mountains I’ve never even seen. Najma received her licence to practice two years ago. But I gave her my licence last week, when she told me about a patient whose family couldn’t pay the bill. She stepped up to foot it instead,” Faizi says. “No award, not even the lifetime achievement award I received from the World Biodiversity Congress in 2015, can compare with the pride I felt when she told me this.”

[ad_2]

Source link